“Was this a courageous act of protest or a sad act of madness? This fascinating book explores the line between inspiration and insanity. The case of Marshall Ledbetter is humorous, chilling, and an important story to tell.”—Gary Alan Fine, coauthor of Whispers on the Color Line

“Was this a courageous act of protest or a sad act of madness? This fascinating book explores the line between inspiration and insanity. The case of Marshall Ledbetter is humorous, chilling, and an important story to tell.”—Gary Alan Fine, coauthor of Whispers on the Color Line

“I could not put down this book.”—George Singleton, author of Between Wrecks

“A compelling look at a significant but little-known incident in Florida history, one that turned out to be a precursor to the Occupy movement.”—Craig Pittman, author of The Scent of Scandal

We are excited to present the true story of a bizarre act of creative crime: the biggest security breach in the history of the Florida State Capitol.

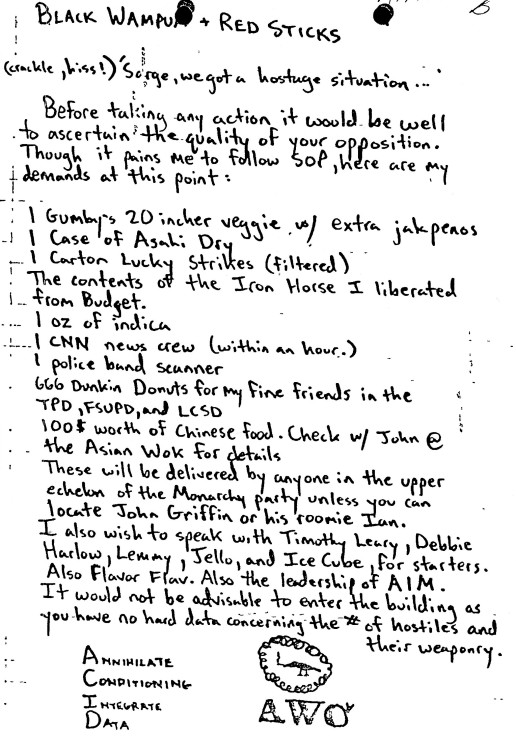

Early one morning in June 1991, after a long night of heavy drinking, Florida State University dropout Marshall Ledbetter used an empty whiskey bottle wrapped in a towel to break through the glass doors of the Florida State Capitol. Occupying the Sergeant at Arms suite, he demanded an extra-large Gumby’s pizza and 666 donuts for the cops waiting outside (Jello Biafra later wrote about this incident in his song “The Ballad of Marshall Ledbetter”). He was making a statement; no one was hurt; he didn’t even have a gun.

In Making Sense of Marshall Ledbetter: The Dark Side of Political Protest, Daniel Harrison tells the story of a young man whose silent struggle with mental illness first manifested in this peculiar public protest, followed by ten years in and out of institutions and his eventual suicide. The book explores the ways society deals with unstable people in real-life situations and whether our law enforcement and justice systems are equipped to handle mental illness.

Intrigued? Here’s an excerpt from the book that we think you’ll enjoy. You’ll get an inside view of the comic crime that has since become tragic legend.

Excerpt from Chapter 7, “Capitol Showdown.”

“This was a declaration of war on the present day power structure of this planet. . . . I was doing my best to invite a world revolution.”—Marshall Ledbetter in Dr. William Spence, “Court-Ordered Psychological Evaluation,” July 2, 1991.

“There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!”—Mario Savio, “Sproul Hall Steps, December 2, 1964.”

Ledbetter arrived at the capitol building a little after 3:00 a.m. He was wearing acid-washed shorts, flip-flops, and a faded purple tie-dyed Jimi Hendrix T-shirt. He surveyed the scene and weighed the advantages and disadvantages of various entry points into the building. He noticed a Capitol Police officer on patrol but evaded her view. He waited for the right time to act.

About an hour later, Ledbetter wrapped a towel around the empty bottle of whisky he had been carrying and approached a doorway. He was on the south side (Adams Street) of the plaza level. He took a roll of masking tape from his pocket and affixed the tape in strips on the door to muffle the noise of glass breaking. Marshall hit the towel-wrapped bottle hard against the glass. The window didn’t break. Marshall hit it again. It still didn’t break. He reconsidered his technique. This time, Marshall tapped on the glass gently, gradually at first with light taps and increasing the force with each swing. He hit the glass six or seven more times. On the final blow, the window shattered. It was 4:04 a.m.

Strangely, no security alert was triggered when Marshall smashed the window. No lights were tripped, no alarms sounded, no automated phone calls were dialed to the police. No black helicopters swept down on Ledbetter from over the rooftops. Incredibly, despite the new capitol building’s technological wizardry, no sensors had been embedded in the building’s glass doors. Even though Ledbetter had struck a major blow to its defenses, the capitol’s computerized alarm system still registered the building as secure.

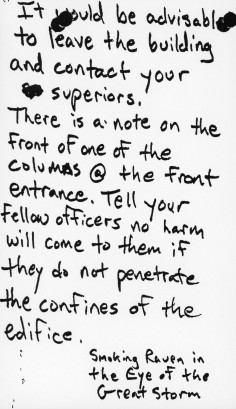

Marshall made his way inside and took a look around. He left one note for police near the entrance and another down the hall. The first note read: “It would be advisable to leave the building and contact your superiors. There is a note on front of the columns @ the front entrance. Tell your fellow officers no harm will come to them if they do not penetrate the confines of the edifice.” It was signed “Smoking Raven in the Eye of the Great Storm.” Marshall made his way to the main lobby and got on an elevator. He rode it up and down for a while before getting worried he might be under surveillance, and so he stepped off.

At around 4:15 Marshall went to use pay phone on the fifth floor. He dialed 911. He told the dispatcher, “The Capitol building is occupied and you will find a note by the door.” The operator alerted Tallahassee Police Department personnel in the area. Two officers and a K-9 dog were sent to investigate. When they got to the capitol, however, “patrol officers were unable to find the broken door and assumed the report was false.” The officers left the premises. It was now about 5:00 a.m. Ledbetter had been amped for a showdown with the police, yet the opposition wasn’t showing up. This must have been maddening for him. Here he was trying to make his stand for freedom, justice, and liberty, and he was getting punked. Where the hell was everybody?

Marshall once again had the capitol building all to himself. He cruised around the empty floors and corridors. His shorts and flipflops must have been holding him back, so he took them off. He found himself in front of room 403, the Office of the Sergeant at Arms (for the Florida Senate). The signage on the door appealed to Ledbetter. It was vaguely militaristic, just like his own name. He tried the door, which to his surprise was open. Apparently, a painting crew had left it unlocked the previous evening. Marshall walked in and made himself at home.

Given the title of the office, Ledbetter might have been expecting to find considerable firepower inside the suite. He would be disappointed. Like his counterpart in the Florida House, the main job of the Sergeant at Arms for the Senate is to keep the wheels of Florida governance running smoothly. According to the Associated Press, “The Sergeant is, officially, in charge of purchasing supplies and seeing to the security of the Senate. Unofficially, the clerks and sergeants in both the House and Senate ensure their own re-elections every two years by meeting—anticipating—the creature comforts of 160 busy, demanding, ambitious people with all the human foibles that the rest of us enjoy.”

Ledbetter looked around the suite. There were two administrative offices and a small kitchen. Marshall decided to barricade the entrance. He shoved a leather couch behind the two large wooden doors to stop them from opening. Marshall went into the office of Wayne Todd, the actual sergeant at arms, and rooted around. He uncovered a box of Hav-a-Tampa cigars and a sizable stash of liquor bottles. Ledbetter removed the tops from all the liquor bottles. He went back into the other room and rifled through the desk of Todd’s office assistant, Julie Anderson. He ate her Captain’s Wafers and made coffee in the kitchen. He knocked over some of Anderson’s treasured African violets growing on the windowsill. Marshall went back to Todd’s office. He poured himself a glass of bourbon, lit a cigar, and waited for the police.

Excerpt from Making Sense of Marshall Ledbetter: The Dark Side of Political Protest. Reprinted with permission from University Press of Florida.

One thought on “Making Sense of Marshall Ledbetter”