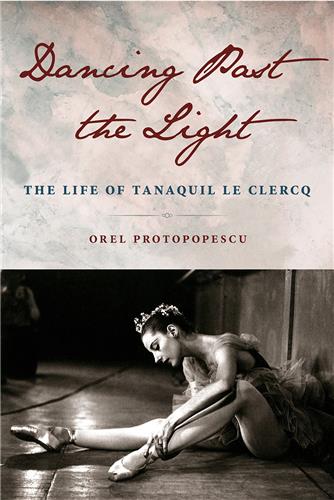

By Orel Protopopescu, author of Dancing Past the Light: The Life of Tanaquil Le Clercq

Today is World Polio Day, which falls during the same month as the birth of the subject of my first biography, the ballerina Tanaquil Le Clercq (October 2, 1929–December 31, 2000). Le Clercq contracted poliomyelitis a few weeks after her 27th birthday while performing with the New York City Ballet on its 1956 European tour. She never danced or walked again, nor did she regain full use of both arms. But when Arthur Mitchell, her friend and former dance partner, invited Le Clercq to teach ballet in Harlem a decade later, she accepted, even though she hadn’t been sure that she could bear to enter a dance studio.

Although she was born in France, Le Clercq was an American, the only child of a St. Louis debutante and a professor of French. She took part in sophisticated productions at the King-Coit school in New York, and by the age of five received a professional review that noted her flair for drama.

Le Clercq was an inspiration to Jerome Robbins and George Balanchine, two legendary choreographers. They both wanted to marry her, but she married Balanchine in 1952, soon after his marriage to the ballerina Maria Tallchief was annulled. Balanchine remained with Le Clercq for longer than any of his other wives, supporting her through one of the most difficult periods of her life. They divorced in 1969.

Robbins remained a close friend, although he and Le Clercq never resumed the intimacy hinted at in letters they exchanged during the tour of 1956. Balanchine had made use of their playful relationship when he cast them in his 1949 ballet Bourrée Fantasque.

The first time I saw Le Clercq dance was at a 2014 showing of Nancy Buirski’s documentary Afternoon of a Faun. When I walked out of the movie theater, I knew that I had to write a biography of this extraordinary woman. As I wrote in the book, “I had never seen a dancer so exquisite, a unique fusion of power and lightness, pathos and wit.” The wit is on display in her writings as well. Luckily for me, Robbins made sure to save both sides of their copious correspondence.

My favorite story about Le Clercq came from her father, Jacques Le Clercq. He had known that his daughter would become a dancer when she was about four years old. Tanaquil had burned her hand on the stove, but instead of screaming, she pirouetted around the kitchen, singing, “This is the dance of the lady who has just burned her hand on the stove.”

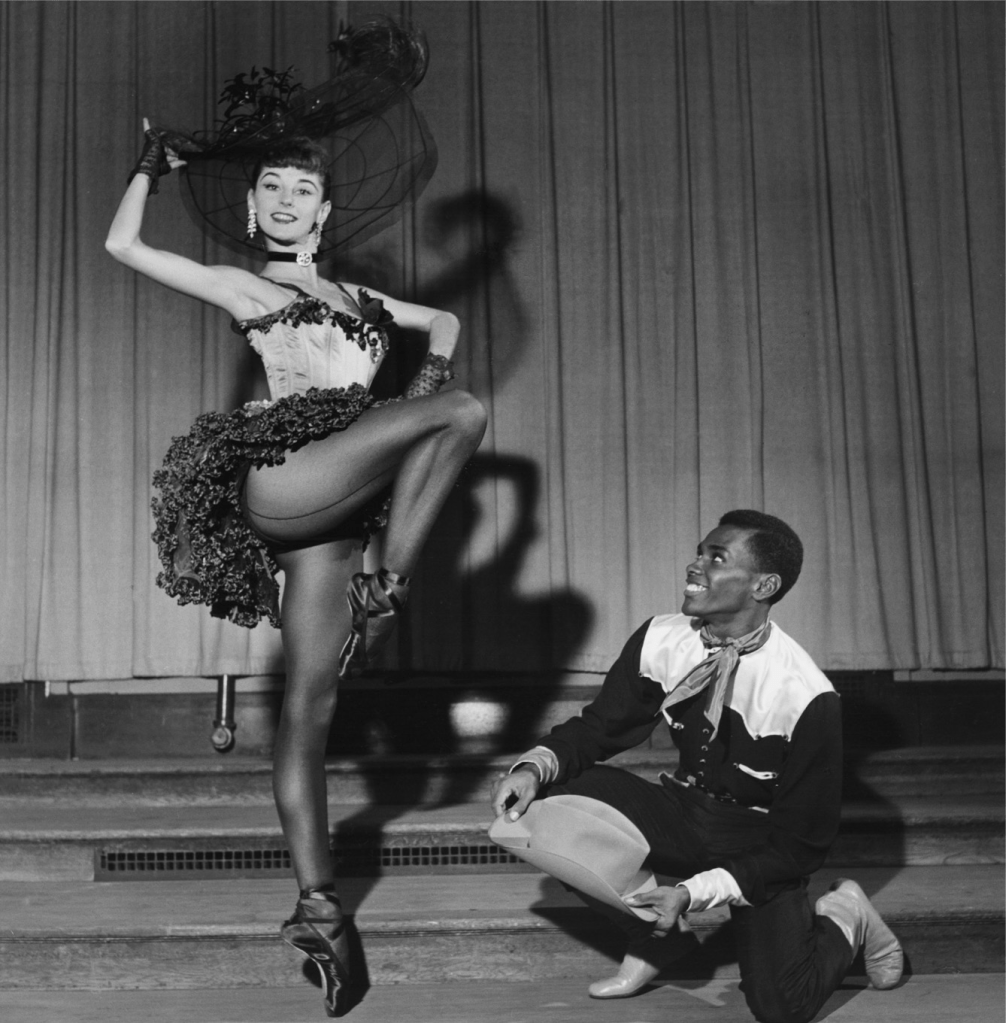

It was clear that at a young age she already knew how to make the best of any hand that she was dealt. More than thirty years later, by using hand signals and her voice, she would teach dance from a wheelchair. In Le Clercq’s words, all attempts to exclude people for any reason were just plain “mean,” a way of framing bad behavior that is simple and direct, as she was. Partnered by Arthur Mitchell, a Black dancer, in 1955, she helped make history in New York City Ballet’s first interracial pas de deux.

For ten years, Le Clercq trained dancers for Mitchell’s fledgling company, Dance Theater of Harlem (DTH). With her dancing fingers, Le Clercq showed male and female students how to move. Decades later, her former students remembered her fondly, with enormous respect. How had she made such a lasting impression? As Theara Ward, a former DTH principal dancer, told me, “She loved us.”

In the 1960s, Le Clercq wrote two books. Her book for children, about a cat who becomes a ballet star, Mourka, the Autobiography of a Cat, was photo-illustrated by her friend, the theatrical photographer Martha Swope. A second publication, The Ballet Cook Book, was a thick tome of recipes culled from Le Clercq’s friends in the dance world, sprinkled with her own photos and witty observations. Le Clercq retained her curiosity, good humor, and passion for life to the end, qualities I celebrate today in looking back at her life. As Le Clercq said to Swope, “People say I’m brave. I’m not. You have two choices. You can be happy or you can not be happy. And I’d rather be happy.”

Orel Protopopescu is an award-winning author, poet, and translator based in New York. Her books include What Remains, A Thousand Peaks: Poems from China, and Thelonious Mouse.

Image credit: Photo by Jan La Roche 2020.